The picture of human pain-sensing nerve cells wins 2nd prize in the DNRF’s Photo Competition 2022

The winner of the second prize in the DNRF’s Photo Competition 2022 is a picture of human pain-sensing nerve cells. The image was taken during a new biomarker study that is going to help cancer patients with their constant pain and sensory disturbances from chemotherapy.

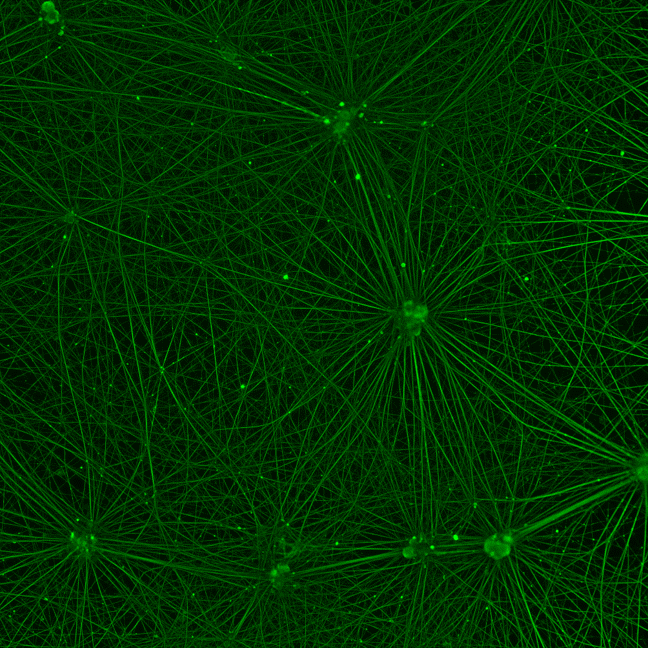

The viewer sees a network of green cells that illustrate a natural cohesion. The image conveys ambiguity: the viewer feels some sort of energy and life, yet the story behind the image is related to pain. The winner of the second prize in the DNRF’s Photo Competition 2022 is a picture of human pain-sensing nerve cells. The image was taken by Ph.D. student Christina Mortensen from the Clinical Pharmacology, Pharmacy and Environmental Medicine Department at the University of Southern Denmark. She took the image during a new biomarker study that is going to help cancer patients with their constant pain and sensory disturbances from chemotherapy. The biomarker study is supported by the Danish Cancer Society.

“The image shows the pain-sensing nerve cells that are normally found in the skin and are responsible for the feelings of pain, warmth, cold, and touch that we experience every day. In our lab, we have developed these pain-sensing nerve cells from human stem cells. The nerve cells are related to a complex network, which is visualized in the green color we see here,” said Christina Mortensen.

A promising result

The side effects that come with certain chemotherapies are related to pain relayed through cells in the skin, and this pain degrades the patient’s quality of life and affects the course of treatment. The painful skin side effects are a growing problem as more and more patients survive cancer and live with chemotherapy’s effects. It is therefore important to focus on preventing these painful skin side effects that result from chemotherapy. A recent study has discovered a new biomarker that can prevent this problem in the future.

“The image is part of a biomarker study that we have almost finished. It shows healthy nerve cells that haven’t yet been treated with chemotherapy. This image works as a control that we use to reevaluate how much damage the chemotherapy causes,” said Christina Mortensen.

In other words, the nerve cells become damaged and will appear different.

“With this picture we show that the biomarker is expressed in the pain-sensing nerve cells. We started out by growing the cells in a Petri dish and then ‘dripped’ chemotherapy on them to see how they reacted. We collected the growth medium that the cells were in, and then we could measure how much biomarker the cells had released. We observed that the more chemotherapy we ‘dripped’ on to the cells, the more biomarker came from the cells. This is a very promising result.”

A new method

Christina Mortensen took the picture while the researchers were developing new methods. When she took it, she was amazed by the beauty of it. The green network of cells helps them see how different patients react to chemotherapy.

“When patients are treated with chemotherapy, it is primarily the damage done to the pain-sensing nerve cells that leads to pain and sensory disturbances. In my project, we use ‘new’ stem cells that can develop themselves into almost all types of cells in the body. What we do in the lab is we push the stem cells in a direction where they turn into the pain-sensing nerve cells,” said Christina Mortensen.

The pain-sensing nerve cells in the picture have been through a process called immune coloring, whereby antibodies are added to the cells and then an image is taken with the help of a fluorescence microscope. The marked antibody will then light up and visualize the pain-sensing nerve cells and their complex network.

“The method that is used in the image isn’t simple, and the following analysis is very complex. We have looked for a more objective method to do this work. The finding of this new biomarker will make it easier to research these painful skin side effects in our cells in the future.”

Prevention of perpetual pain and sensory disturbances

While the research group was moving in the right direction with the cell studies, they were interested in confirming their findings by working with clinical data from the beginning. This was made possible by a collaboration with Sygehus Lillebælt hospital.

“In our research group we are focused on translational work. This means that we want to combine our findings in the lab with clinical data. That is why we established a collaboration with Doctor Karina Dahl Steffensen, a clinical professor in the oncology department at Sygehus Lillebælt. We have examined the potential of the biomarker in blood tests from patients with ovarian cancer that is being treated with paclitaxel. It looks like we can predict early on which patients will develop nerve damage and constant pain.”

The research group is currently working on confirming that the biomarker can be used in children with leukemia who are being treated with vincristine. The group is working in conjunction with Kjeld Schmiegelow and René Mathiasen at the children’s oncology department at Rigshospitalet.

“It is important that our findings from the lab be confirmed with the patients. This way we can confirm the relevance of our research.”

The hope is that this work will help to prevent cancer patients from experiencing painful skin side effects that follow treatment with chemotherapy. Once the biomarker is validated in more studies, it will be possible to use it to diagnose and monitor patients’ conditions over time.

“In the future the biomarker will help guide the clinical decisions and help them customize the treatment to the individual patient,” said Christina Mortensen.

The scientific study with the biomarker isn’t finished yet, so there isn’t a release date at the moment.