New study from CEBI: Parents’ birth weight influences children’s performance in school

The correlation between one’s birth weight and how one makes it later in life is not a new phenomenon within science. According to a new study, researchers, for the first time, have linked differences in parents’ birth weight with differences in their children’s performance in school. Behind the study are Professor Hans Henrik Sievertsen from the University of Bristol and Professor Claus Thustrup Kreiner, head of center at the Center of Excellence CEBI at the University of Copenhagen.

From the moment we are born, a number of factors can predict how we will make it later in life – including how much we weigh at birth.

The correlation between one’s birth weight and how one will make it is a well-known phenomenon within science. Now, a research team has, for the first time, taken it one step further and examined whether inequality within one generation is traceable in the next generation. Professor Hans Sievertsen from the University of Bristol and Professor Claus Kreiner, head of center at the DNRF’s Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality (CEBI) at the University of Copenhagen, are behind the study that connects differences in birth weight in one generation with differences in their children’s school performance. The study, which is a working paper, has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Health Economics.

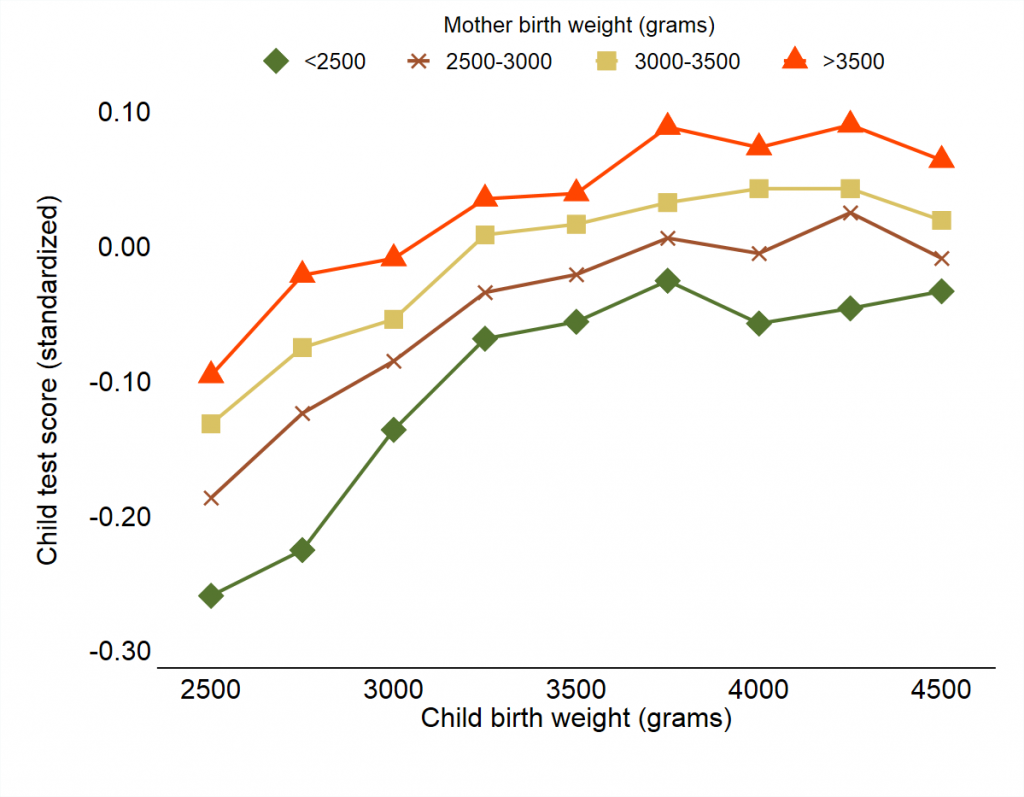

“Our study shows that there is a correlation between the mother’s birth weight and how well the child performs in school – including when we take notice of the child’s birth weight. We already know from previous research that a higher birth weight among parents can predict the birth weight of the child. Our results show that regardless of the birth weight of the child, it will perform better if the mother had a high birth weight,” said Professor Kreiner.

A large register study

The study is based on a comprehensive amount of data covering more than 895,000 observations, with 226,000 being the birth weight of mothers and their children. The enormous data set primarily comes from the birth register at Statistics Denmark. The register covers every parent born after 1973 and their children born between 1995 and 2007. The birth weight from the 226,000 mothers and children was compared with the children’s test results from national tests from 2nd to 8th grade.

“We measured the children across all subjects, but the correlation still exists, if we look at the results separately from subjects such as Danish or mathematics. The study is fundamentally about how much is predetermined to some degree. The variation we have examined regards how the children perform in school that further have consequences for the rest of their lives,” said Professor Kreiner. He added:

“When you measure inequality as we do here at CEBI, then you are interested in the degree of persistence, which means how persistent the inequality is across generations. In that sense, this study suggests that there is a so-called intergenerational persistence meaning that there is a variation between the mothers that not only has a consequence for how the parents themselves make it in life, but also has a consequence for the children.”

Together with Professor Sievertsen, Professor Kreiner also examined fathers’ birth weight. Since women are biologically closer to the child and since it typically is the mother who spends the most time with the child during the first days after giving birth, the researchers expected that there would be a more dominant correlation between the mother’s birth weight and the child’s performance.

But from the data set with the birth weight of both parents that was available to the researchers, Professor Kreiner and Professor Sievertsen found that the correlation between the mother’s and the father’s birth weight was equally important for the school performance of the child.

However, it must be noted that the researchers had a significantly smaller sample for the fathers. The reason is that men, on average, are older than women when they have children, and therefore, it is not possible to gather the same amount of data from the fathers as with the mothers.

Nature and nurture

To find the underlying mechanisms behind the correlation, the researchers tried to separate nature and nurture as the two main components. Therefore, the researchers compared data from mothers who are sisters and who share the same family background. Here, the results showed that the child of the sister with the highest birth weight performs better in school than the child of those sisters who had the lowest birth weight. In that way, the researchers were able to remove their family background as a component and thus gain a better insight into how powerful the correlation is between birth weight and the child’s school performance.

“We still observe a rather strong effect. The correlation between the mother’s birth weight and the school grades are about fifty percent of the correlation between the child’s birth weight and the child’s school grades. When you keep the family background out of the picture, then the difference in birth weight results in prolonged consequences than what we believed before,” said Professor Kreiner.

Nevertheless, the researchers cannot reject the family background and nurture component entirely as a possible reason why children of parents with a high birth weight, on average, perform better in school. According to Professor Kreiner, the correlation between the maternal birth weight and the child’s school performance can be explained by a direct nature mechanism that goes through the genes, so to speak, but it can also be explained by a more environmental nurture mechanism, for example, if a mother with a higher birth weight invests more in her child and raises the child to perform better in school. Or it can be both.

“The mechanism can come from both; we cannot separate the two. But what we can say is that there is a social inheritance that is created already when the mother is born. The inheritance can predict how well children from the next generation will perform in life,” said Professor Kreiner.

From one generation to the next generation

The next step for the research team is to examine the degree of so-called intergenerational effects – effects from one generation to the next generation. More specifically, it is the researchers’ ambition to dig deeper into the underlying mechanisms behind the correlation between the birth weight from one generation of parents and the cognitive performance in the next generation of their children.

“We would like to examine if the inequality there is – is part of the social inheritance that traces back to the previous generation. This is where this study is relevant because it shows that there are persistent consequences that we have not seen before in the correlation,” said Professor Kreiner.

Besides the underlying mechanisms, the researchers hope to examine other outcomes in the child such as choice of education, their first job, and how the child will be placed in income distribution. In that way, the researchers will be able to see whether the correlation between their observations from this study continues throughout the child’s adult life.

“Usually, we see that the ones who perform well in school are also the ones that, in different ways, get a better life economically. They get a higher income, are less unemployed, and less exposed to various kinds of accidents. This will be possible to measure in 10-20 years when the children are older, so it is far out in the future,” concluded Kreiner.

Read more about the study from CEBI on the center’s website here