CMEC and Center for GeoGenetics are part of developing a method to fight snail fever

A method developed by researchers from the University of Copenhagen can track the feared snail fever parasites in water samples, a new study in PNAS shows. The study was carried out in a collaboration between researchers from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, researchers from Kenya, and the DNRF’s Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate (CMEC) and Center for GeoGenetics.

A research team from the University of Copenhagen, including Assistant Professor Anne-Sofie Stensgaard from the basic research center CMEC, researchers from the DNRF’s Center for GeoGenetics, and researchers from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, is behind a study recently published in PNAS. With the help of a new method based on eDNA, the researchers were able to track the feared so-called snail fever parasites in water samples. This new way of tracking will contribute to fighting snail fever parasites, which cause more than 200,000 deaths each year.

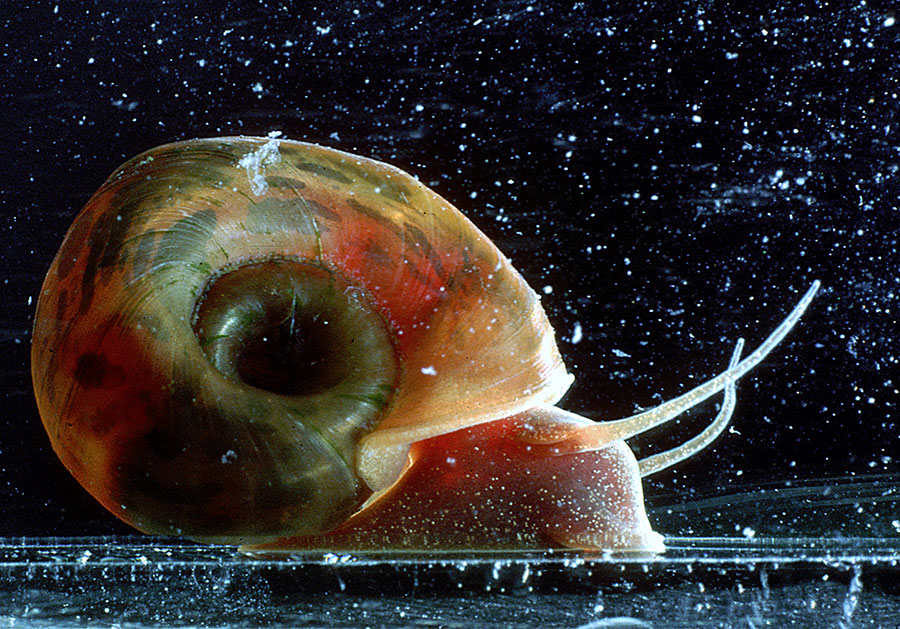

The parasite larvae are liberated from the snails and swim around until they find a human host. Then they penetrate the human skin and, feeding off the bloodstream, they copulate and produce thousands of eggs. An infection from these parasites can lead to blood loss, tissue and organ damage, as well as learning difficulties in children. The parasite larvae are so small, they can hardly be seen with the naked eye, which makes detecting the larvae tricky.

But with the method based on eDNA – also called environmental DNA –developed by Mita Sengupta from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, the researchers can identify molecular fragments from dangerous parasites directly in a water sample without seeing the tiny larvae. Therefore, the method can be an important tool in the fight against the infectious disease schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever.

“This is a big step towards an improved surveillance of the very overlooked parasite disease. Until now, the method to detect parasite-contaminated water in tropical and subtropical areas has been to find the snails that function as a medium and examine them visually for these tiny parasite larvae. It is a slow process that demands researchers with expert knowledge about snails,” said Sengupta.

Together with Kenyan partners, the Danish researchers compared the new environmental DNA method with the conventional method in a collection of snails from water areas in central Kenya, where many people suffer from the disease. The lab analysis showed that the new method was able to identify parasites in more areas than the conventional method.

“Compared to the traditional method of collecting snails, the new environmental DNA method has the big advantage that it can discover transmission even in areas where one would find very few infected people and no infected snails. This makes the method an important tool in the fight for eliminating this parasitic disease from many areas in the tropics. Since the disease was recently detected on Corsica, the new method will also be useful in the surveillance of the spreading of the disease to areas outside its normal geographical dispersal because of climate changes and an increased human migration flow,” explained Stensgaard, an Assistant professor at CMEC and senior author on the study.

Read the scientific article in PNAS here

More information about the study can be found in a press release from CMEC here