CEH examines how captivity affects the gut in animals

What happens to animals’ guts when the animals are removed from their natural environment and placed in captivity? This is the topic of a new study from the Center of Excellence Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics (CEH) at the University of Copenhagen. The researchers examined the gut microbiota in wild animals and compared them to the microbiota of animals in captivity. The results of the study varied, making it apparent that there isn’t one simple answer to this question. The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

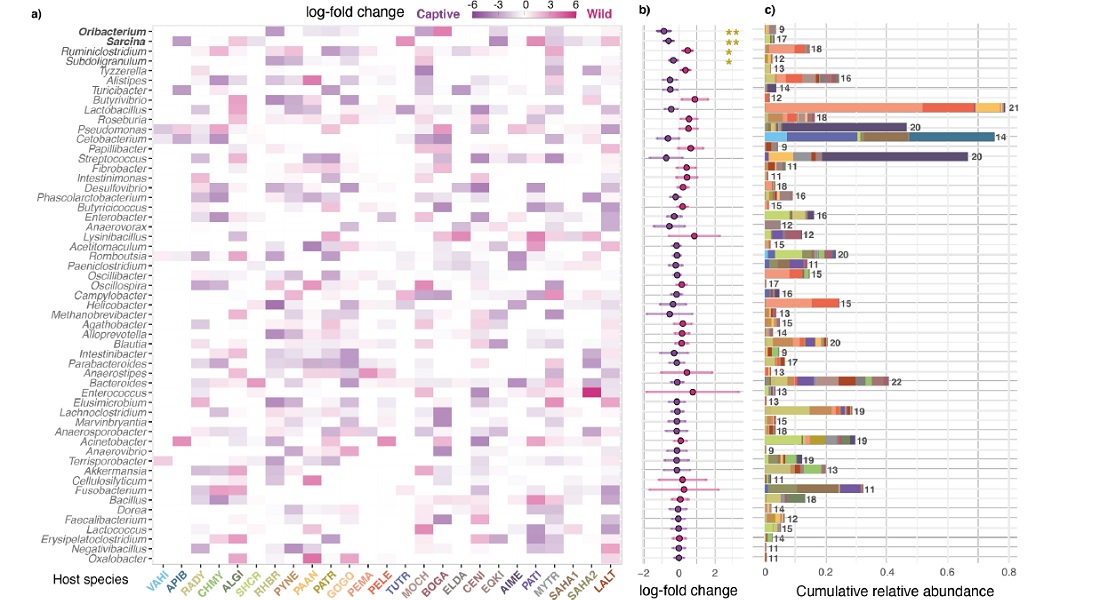

What does the transition from living in the wild to living in captivity do to an animal’s gut microbiota? This is one of the questions that researchers from the Center of Excellence Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics (CEH) at the University of Copenhagen tried to answer in a new study that was recently published in the journal Scientific Reports. In trying to answer this question, researchers compared the so-called gut microbiota between wild animals and animals in captivity. It turned out that while there is a change in the gut microbiota, the changes are diverse rather than homogeneous.

“So far, there was no systematic meta-analysis on whether and how captivity induces directional changes in the gut microbial communities associated with animals, just a collection of dozens of publications with different study designs and aims. In this study, we have gone through over 200 publications and reanalyzed the available data to try to detect overall variation in microbiota patterns,” said Associate Professor Antton Alberdi from CEH, who is first author on the study. Research Assistant Garazi Martin Bideguren and Assistant Professor Ostaizka Aizpurua from CEH are co-authors on the study.

No simple answers

Since the results about the composition of the gut microbiota were so diverse, the researchers did not come to any conclusions or find any simple answer. Surprisingly, a large number of human-associated microorganisms were found in the captive animals, but it was impossible to assess whether these microorganisms drove out their wild counterparts or if they simply fill the void that was left behind.

“On the one hand, our studies indicate that no rule of thumb can be applied to predict what will happen with the microbiota of animals taken into captivity. It seems clear that, usually, the microbial diversity initially drops, yet after some time, it might fully recover or can even exceed that of wild counterparts. On the other hand, the lack of relevant metadata complicates associating the observed patterns with management features such as diet, the environment, or the use of medicines, which could contribute to increasing our understanding of why microbial communities change in one way or another,” said Associate Professor Alberdi.

The study concluded that researchers should be cautious about using the available data when addressing evolutionary questions concerning wild organisms, at least until it is possible to systematize the data better.

Read the article in Scientific Reports here

Read more about the study at KU here